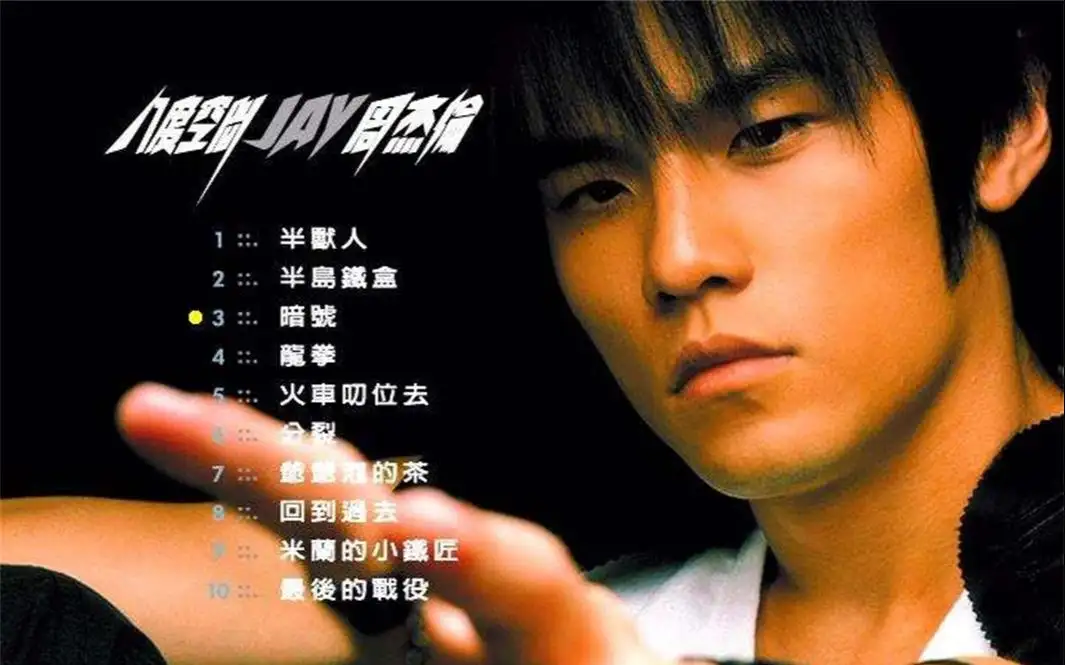

For me, Jay Chou’s The Eight Dimensions is an absolutely mind-blowing album. When most people think of his ‘god-tier’ albums, it’s almost always one of Jay, Fantasy, or Ye Hui Mei, nine times out of ten. There’s even this saying in the music world that genius musicians are done after three albums (and speaking of which, you can’t help but think of those artists who truly peaked right out of the gate!): the first is groundbreaking, the second is a massive hit, and the third is just a desperate struggle. Of course, Ye Hui Mei later totally proved that Jay Chou’s creative genius was nowhere near limited to just three albums. By the time Common Jasmine Orange and November’s Chopin came out, his popularity had soared to new heights again. But I still gotta say, The Eight Dimensions is a real outlier for Jay Chou. Among all his legendary, peak albums, it’s the one that feels the least ‘Jay Chou-esque.’ It has such a unique and rich vibe, an unconventional concept that explores so many different angles – I seriously never ever get tired of listening to it.

But hey, why am I even talking about Jay Chou on a Cantonese blog, you ask? Because he seriously had a huge impact on my musical journey. Whether it’s the sheer breadth or the depth of his music, he’s got so many solid, standout tracks. And honestly, after the millennium hit, there just aren’t that many Cantonese singers worth mentioning anymore. As for Alan Tam and Jacky Cheung? Well, they’re practically ancient legends, like mythical beasts from another era!

Half-Beast

The intro, with its strings and horn calls, is absolutely epic and carries a hint of desolation – that’s all thanks to the underlying woodwind and brass sections, and those ‘dong-dong-dong’ timpani beats in the middle don’t just keep time, they give it the vibe of an epic movie opening! Seriously, these forty-something seconds of intro could totally be the album’s official ‘Intro.’ In fact, it was Jay’s first time playing with an album opening ‘easter egg’ like this. What’s really cool is how this intro totally echoes ‘The Final Battle’ at the end of the album. Both tracks use those poignant brass sounds, instantly unifying the whole album’s tone. Later on, ‘In the Name of the Father’ from Ye Hui Mei used a similar technique for its opening, but it doesn’t really seem to echo the overall vibe of that album, does it? (Seriously, what was the vibe of that fourth album anyway?)

After that storm of strings, a few heavy drum beats mixed with ‘shhh-shhh’ scratching sounds crash in, officially drawing back the curtain on the Half-Beast world. Listen closely, and besides the staccato violins, there’s an underlying piano subtly surging, pulsing in sync, like a shared heartbeat, with the strings. Speaking of which, even though Jay’s a rhythm genius, he’s never stingy with his arrangements’ layers – no wonder his songs are endlessly re-listenable. When it comes to the verses, you get that classic Jay-style flow paired with Vincent Fang’s wonderfully fantastical lyrics. And especially that rhythmically displaced bridge before the first chorus – it’s just so cool! This kind of ‘playing around’ that pops up now and then is super fun, and it’s totally similar to the modulation at the end of ‘Blue Storm.’ As for the chorus and outro, the brass section performs as expected. The whole song is actually packed with clever, hidden arrangement tricks, but it’s a shame not many people seem to appreciate those details.

Peninsula Iron Box

After ‘Half-Beast’ came storming in with that powerful opening, Jay Chou chose a slow song to follow it up. The melody is just so smooth and natural, the rhythm harmonious and flowing, with those sad guitar notes weaving through a chill, almost nonchalant vibe. The busy hi-hats sound like subtle rustling, like a quiet whisper, hinting at a slight unease beneath the calm strings. And through all the constant key changes, it builds this sense of emotional hesitation and loneliness, with the emotions just simmering and intensifying as the song goes on.

Oh, and by the way, the mixing on this album was a massive leap forward! While it didn’t quite hit that ‘big production’ level of later albums like Common Jasmine Orange and November’s Chopin, overall, they totally nailed it. As for the arrangement of ‘Peninsula Iron Box,’ even though there aren’t a lot of flashy tricks to pick apart, it’s actually one of those rare tracks from Jay Chou that isn’t overly ‘decorated’ or ‘busy.’ The emotional expression is perfectly controlled and just cuts deep, hitting you right in the feels. Honestly, in this fragmented age we live in, it’s probably a tall order to hear such pure new works again.

Secret Signal

“Secret Signal” is pretty much a classic Jay-style R&B love song, following a similar formula to “Love Before BC” from his previous album. The overall vibe is still that melancholic feel, but this time, the emotional rollercoaster is way more intense! He really pulls off those frequent transitions between his chest voice and falsetto, even within a relatively narrow range – he totally delivers there. And that bridge part, with the falsetto that almost sounds like he’s tearing up, combined with the super smooth key change? It just makes the whole song really come alive!

But honestly, compared to his earlier stuff, this song definitely feels like it’s missing a bit of that signature ‘Jay Chou’ touch. It’s one of the rare tracks on the whole album that feels a bit… well, ‘assembly-line’ or just a bit plain. Thankfully, that falsetto in the bridge is just so gorgeous, it makes the whole song way more enjoyable and re-listenable. Maybe it’s all thanks to that legendary live performance, perhaps?

Dragon Fist

After “Nunchucks” became a massive hit, Jay Chou really found his groove with that Chinese-style + rock combo, so much so that his next album even had a similar track, “Double Blade” (though I’m guessing “Double Blade” didn’t land as well, which is why Jay shelved that style for a while, only bringing it back for “Huo Yuan Jia”?). The song kicks off with drums, then suddenly throws in an unexpected scratch, followed by an explosive electric guitar that just blasts right into your ears. In this part, Jay Chou’s signature four-tone rap, combined with Vincent Fang’s lyrics, is an absolute perfect match! The verses are incredibly groovy, then it transitions to a guzheng section, giving listeners a moment to breathe. When it hits the bridge, Jay starts playing around again – that one line, “Wait a minute,” immediately shifts the song’s whole groove, leaving some lingering charm amidst the onslaught. The whole song has these big ups and downs, but it’s not as dazzling or overwhelming as “Turkish Ice Cream,” and placed in the middle of the album, it really has this refreshing and invigorating effect.

Where’s the Train Going

After catching a breath, the album goes right back to that head-nodding, immersive vibe. The mumbling rap, mixed with Hokkien, easily conjures up those old-time story scenes. The clanging sound of a train hitting the tracks at the beginning instantly pulls you back to slower, old times. The arrangement might seem simple, but it hides so many clever details that make you addicted to listening. Even though the name sounds similar to Luo Dayou’s “Train,” they’re totally worlds apart. “Where’s the Train Going” isn’t as passionate or stirring as “Train.” Its muted atmosphere, echoing harmonies, and drum patterns that sound like clanging train tracks all come together to form a truly unique Hokkien song. The biggest pity is that Jay never released anything similar afterwards – in my heart, it’s truly an undiscovered gem.

Split

This is a rare moment where Jay Chou really opens up, baring his soul in this song. He relies on the emotional layers of just a few chords to build up this sense of vulnerability. He doesn’t package himself as an omnipotent strongman here; instead, it’s about the helplessness he feels as time and memories fade, continuing that consistent sense of disorientation and loss from earlier tracks like “Peninsula Iron Box” and “Secret Signal.” Looking back at his later albums, he started to get a bit ‘inflated’ (and I don’t mean that negatively) – he’d say not getting awards was the Golden Melody Awards judges’ problem, he’d vow to be the emperor of music, he’d emphasize he was a superman. But listening back to this song, I realize this is Jay Chou’s rare inner monologue after taking off his halo and experiencing hardships as an ‘ordinary person.’ It also adds this lingering, drawn-out emotion to the song. The whole track might be simple to the point of being bare, but its strength lies in its authenticity. It’s precisely this raw sincerity that gives the song its unique flavor.

Grandpa’s Tea

“Grandpa’s Tea” just gives you this super light and airy feel, kind of like the refreshing, carefree vibe of “Simple Love.” The arrangement is totally Michael Lin’s signature, most comfortable R&B groove too, with those crisp drum beats paired with Jay Chou’s surprisingly clear and distinct vocals. Seriously, in a nutshell: it’s pure comfort, pure bliss!

Return to the Past

When it comes to “Back to the Past,” the guitar and string arrangements are still unbelievably smooth, but just like “Secret Signal,” it goes for that light and cheerful vibe, which honestly isn’t my cup of tea. (I feel like this song is super polarizing; people who love it cherish it like gold, while those who don’t ‘get it’ feel absolutely nothing – basically, I just said nothing useful, haha!)

The Little Blacksmith in Milan

“The Little Blacksmith of Milan” might remind you of the songs he wrote for Jolin Tsai around the same time. The scratching and various sound effects are purely there to add flavor to the song, keeping listeners from getting distracted. The muffled atmosphere that seeps out from the MIDI brass in the intro is like a storybook opening, first introducing the setting, instantly making you see a cloudy day in Milan. Then the guitar suddenly perks up and jumps, that bouncy feel almost like it’s depicting the little blacksmith’s proud and swaggering look. After the chorus, a “creak” as the tavern door closes, and the little blacksmith sits still, listening to the performance on stage. Unconsciously, his mind is playing a scene of himself on stage one day, with thunderous applause below. But then a few dog barks pull him back to reality, and that final “baa” really has a touch of an O. Henry ending.

The Last Battle

“The Final Battle,” compared to “Wounds of War” two years later (which also served as a grand finale and talked about war), puts an even deeper and grander period on the entire album. Of course, following “The Little Blacksmith of Milan,” it also fits well with the restrained melancholic undertone from earlier in the album. The vocal delivery change in the second verse makes the whole song even more re-listenable, and that Scottish bagpipe at the end is Jay Chou’s signature exotic sound trump card. But paired with the strings’ lively major key arrangement, it’s contrasting yet doesn’t feel contradictory. The album reaches this point, continuing that perfectly executed closing vibe from his first two albums.

In my eyes, aside from those two songs whose positioning feels a bit redundant and awkward, The Eight Dimensions is truly an album worth savoring slowly. Maybe the remaining eight songs actually correspond to the album’s title? No matter what, if I had to pick a Jay Chou album to accompany me, this would definitely be my first choice.